*The following review for Disfigured On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space contains Amazon affiliate links. As an Amazon affiliate I earn a commission on qualifying purchases.

Within Disfigured On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space author Amanda Leduc explores western fairy tales and the role disability plays in the narrative. As Leduc explains in her “Introduction,” “Disfigured is my attempt at unravelling some of the more well-known Western fairy-tale archetypes in light of a disability rights framework.” Throughout the book Leduc intertwines disability’s presence in fairy tales and their purpose in molding the stories with her own firsthand experiences with mild cerebral palsy (CP) spastic hemiplegia and more.

That more includes research into fairy tales and insights from others in the disabled community. The latter gives Disfigured extra credibility by supplying multiple people’s takes on the subject, not just her own. Nonetheless, numerous individuals make up any given community. Different individuals possess different opinions and as such no one community shares a completely unanimous stance on a single issue.

Simultaneously varying opinions means opportunity for conversations. Disfigured certainly offers much to discuss. Shall we begin?

Getting the Conversation Started

Discussions often work well when the parties involved can bond over similar experiences. Also having mild CP spastic hemiplegia, I related a lot to Leduc. Yet, I believe anyone in the cerebral palsy or larger disabled community will find something from Disfigured relatable.

As Leduc illustrates throughout the book, fairy tales fail to make disabled life feel desirable. Differences either show up as an obstacle to overcome or a way to establish a character as a villain. Such a portrayal will sabotage anyone’s confidence. Hence why one day after a particularly rough day at school, Leduc recalls in Chapter 7 “The Desolate Land,” “Why can’t I be like everybody else? I said to myself when I went home that night years ago. Just like Hans My Hedgehog, just like The Little Mermaid.”

Similarly, early in my first memoir Off Balanced, I recount losing an argument with my parents about using the elevator at school. To ensure I at least received the last word I stormed up to my room. Remembering back on the moment I wrote, “I brewed in anger at my parents and grew more agitated with my life’s situation. ‘Why did God give me cerebral palsy?’ I asked myself over and over. Yet no answer seemed to exist.”

Flashing back to my own words from Off Balanced actually emphasizes Leduc’s point about how fairy tales positions disability as an obstacle to overcome. Like if a reason or moral existed to why I had CP, then I could move forward happily ever after.

Happily Ever After

Ah! That happily ever after fairy tale ending heavily connected to the genre. Especially once Disney put their touch onto the stories, as Leduc notes in Chapter 4 “Someday My Prince Will Come: Disney and the World Without Shadows,” “The ‘Disneyfication’ of well-known fairy tales – wherein the happy endings become even happier.”

These happy endings reoccur as a theme throughout Disfigured. In Chapter 5 “The Little Dumb Foundling: Hans Christian Anderson’s Ugly Little Ducklings,” Leduc summarizes, “The end goal is always the same: the happy ending somehow always involves a body that does exactly what it’s supposed to do all of the time.”

A little earlier in the chapter Leduc gives a powerful comparison, comparing her own experiences with The Little Mermaid’s Ariel, writing, “Ariel, of course, gained her legs by magic. I gained my legs by the decidedly less romantic practicalities of orthopedic surgery, practicalities that left me with a limp that wouldn’t go away. Unlike in Ariel’s case, the acquisition of my legs was not picture-perfect.”

Leduc continued, “And as much as I wanted to believe it to be so, the happy physical ending I thought I had acquired by the virtue of surgery and therapy was not, in the end, the kind of happy ending that was talked about in the stories I saw onscreen.”

Reality Check

If reading the above passage leaves you thinking, “They’re just stories!” Leduc anticipates your criticism. Multiple times over the 200-plus pages, Leduc voices and addresses the anticipated feedback.

Personally, I found myself conflicted. Going back and forth over how to react over the happy endings concept. Younger me resonates with Leduc’s comments. I possessed a similar outlook to a surgery I had at 14 years old, writing in Off Balanced, “My curved posture was one characteristic which made me standout in a crowd. The surgery would fix that. I decided to use my corrected posture as a launching point for becoming physically stronger. I was already using my mother’s stationary bike to strengthen my legs. If I started lifting weights during the summer, I could bulk up my spider-like arms and enter high school taller and stronger than ever before.”

Just like Leduc, I expected surgery to give me a happy physical ending. Instead, complications left my right leg temporarily paralyzed. Rather than “taller and stronger than ever before,” I entered high school walking with a cane. So much for my happy physical ending.

Yet the surgery aftermath, recovery from paralysis, and lived experiences I continued to garner combined with books I read over the years and engaging conversations with others led me to a realization. One which frequently echoed in my head while reading Disfigured. “Happy endings do not exist!”

The Actuality

Rather the “happy ending” concept stems from a perception issue. For instance, take Leduc who recalls in Chapter 5 “The Little Dumb Foundling: Hans Christian Anderson’s Ugly Little Ducklings,” “My own ideas of love and romance always involved a white wedding dress and a handsome prince, and they always involved standing.”

Such a picturesque wedding day might end a fairy tale, but life itself proves more complicated. In life weddings begin a new story. A relationship levelling up. Challenges, whether arguments over money or a crying newborn disrupting sleep patterns, become inevitable. Placed into perspective, happily ever after gets exposed as nonexistent.

Admittedly, Leduc hints at this in the book’s “Afterword” writing, “The end of a story is not so much an ending as it is a departure – the point at which the audience stops travelling alongside the protagonist and allows them to continue their way through the world.”

Drawing parallels to the disability narrative Leduc adds, “We need to understand that the ‘ending’ of the disability narrative need not come with either restoration of able-bodiedness or a descent into despair at the removal of able-bodied life. Instead, disability narratives and disabled lives deserve to continue as they are, moving forward equally in the realms of joy, frustration, sorrow, anger, and all of the other elements that make up the complex reality of living.”

Changing the Narrative

To show the “restoration of able-bodiedness” narrative seeps into our world, I could list varying firsthand experiences. Others alluding to my movements as “struggling” because I walk different. Another person once introduced me to someone else by saying, “Zach is the most non-disabled, disabled person I’ve met.”

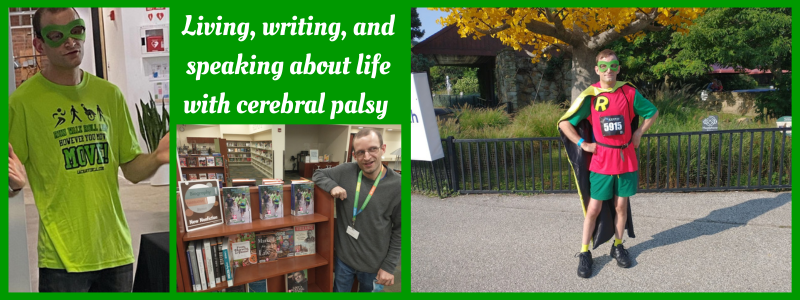

The latter subject also gets covered in Disfigured when Leduc ponders what exactly letting your disability define you means. Once more a relatable topic as I discuss in my second memoir Slow and Cerebral my own initial hesitation to take on my “Cerebral Palsy Vigilante” moniker. Detailing, “Initially, I held off. Not wanting to define myself by my diagnosis.” Realization eventually hit me though, “Owning the Cerebral Palsy Vigilante moniker did not leave me defining myself by my condition, but rather quite the opposite! Helping to show what remained possible. Essentially, defining CP.”

Some might dare to describe Slow and Cerebral as me “overcoming” my cerebral palsy to walk 26.2 miles and become a marathoner. Fitting the able-bodiedness narrative fairy tales contain. However, I purposely avoid the term “overcome” in describing the book since my CP still remains. Rather I worked with my CP to achieve the goal.

Admittedly, I fell along the way. Both in training and race day. Falls which occurred although I used my cane and arranged with the race organizer for extra time. My marathon journey echoes what Leduc writes in her “Afterword,” “Nothing is perfect in the disabled stories we tell, or the disabled lives we live out in the world, and capturing these imperfections is a key part of telling our stories properly.”

Highlighting Imperfections and Making Disfigured Beautiful

By capturing the falls I experienced in training and on race day as well as my internal debate over whether to use my cane for the marathon, I believe Slow and Cerebral meets Leduc’s call for telling proper disabled stories. Although, I am not here to plug my books. Instead, let me finish reviewing Disfigured.

While I wrote quite the lengthy review, much remains uncovered. However, I will refrain from continuing and simply say this. If anything I said today about Disfigured by Amanda Leduc intrigued you, I recommend reading the book for yourself.

Or, did you already read the book? Tell me what you thought in the “Comments” below.

Until next time, remember. Don’t blend in. Blend out!

-Zachary